By Larry Clinton, Sausalito Historical Society

Due to a reversal of fortunes, the heirs of Sausalito founder William Richardson were forced to sell portions of their Rancho del Sausalito to an attorney Named Samuel Throckmorton. In his book “Moments in Time,” Jack Tracy describes Throckmorton as “well known for his clever financial manipulations.”

Throckmorton and his partners formed the Sausalito Land & Ferry Company in 1869 to develop the property, and here’s Tracy’s account of how they changed this area into a full-fledged town:

The Sausalito Land & Ferry Company set to work soon after the land was purchased. They had a survey made and a map drawn up showing future streets and lots available to the public. They named the streets mainly in honor of themselves and quickly staked out prime lots for their villas overlooking Richardson's Bay. They sent one of their number, John L. Romer, off to purchase a ferryboat.

The first streets graded and opened for business were a section of Water Street and Princess Street, named for the little steamer the company had purchased. This area was envisioned as the hub of a business district, with residences to be built on the view lots.

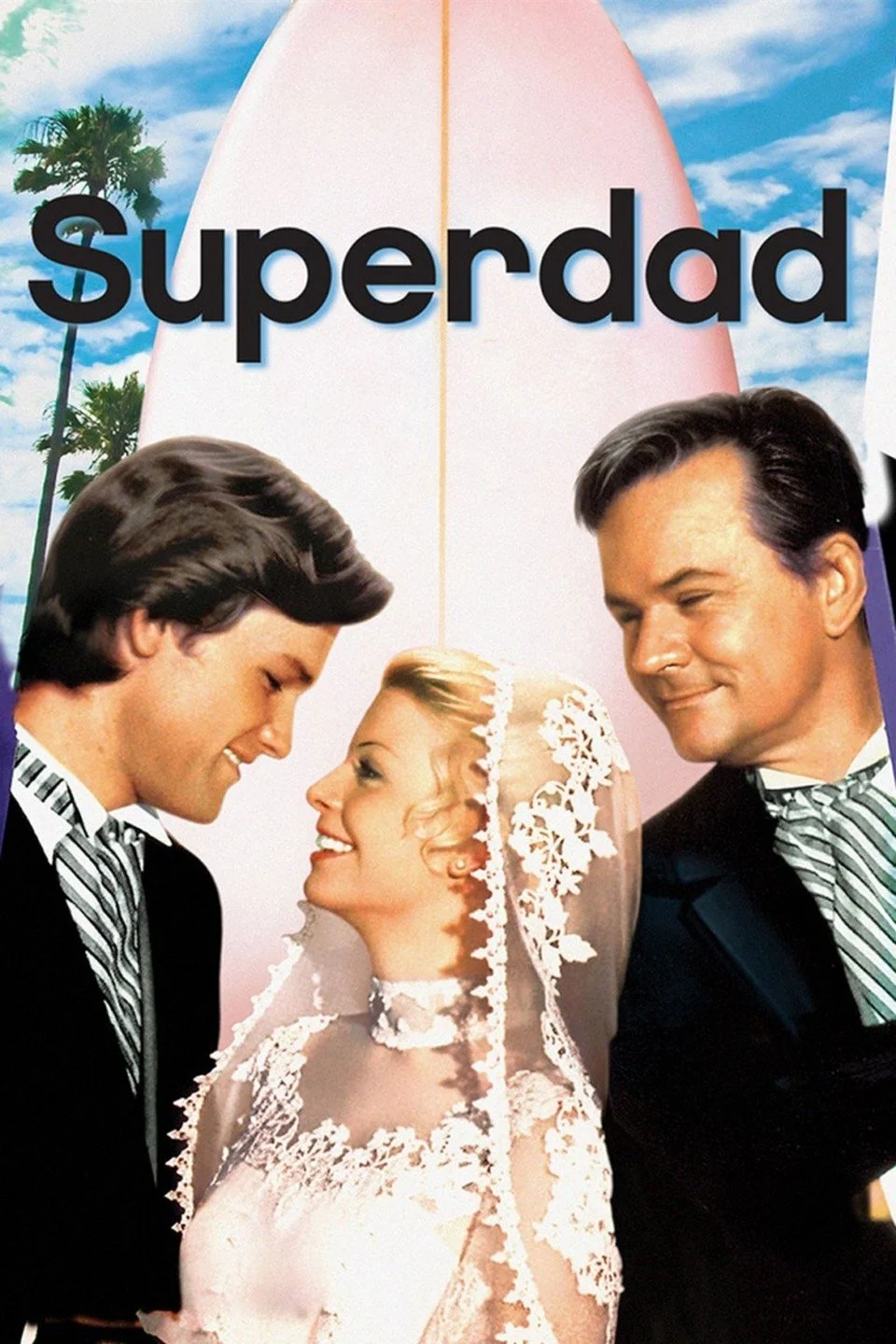

"New" Sausalito from the North Pacific Coast Railroad wharf, looking south c. 1875.

Photo by English photographer Edward Muybridge, courtesy of Sausalito Historical Society

The Princess was launched September 14, 1858, destined for a career on the Sacramento River. Designed to haul freight and a few passengers for Coffey and Risdon, she was 130 feet long with a 21-foot beam and twin 18-foot paddle wheels. The Princess was purchased by the Sausalito Land & Ferry Company just days before her inaugural voyage as a ferryboat on May 10,1868. She made two trips a day from the Princess Street landing to Meigg's Wharf in San Francisco. When the North Pacific Coast Railroad took over ferry operations in 1875, the Princess was sold and five years later was broken up for scrap.

Thomas Wosser was the first engineer on the ferryboat Princess and first of five generations of Wossers who served on ferryboats. He was born in Ireland in 1828 and came to San Francisco around Cape Horn in 1849. Hired as a boatman by Charles Harrison in 1851, he remained in that capacity until his retirement in 1896. He built one of the first homes in New Town, where he lived with his wife and fourteen children until his death in 1900.

The prospects looked good to the men of the Sausalito Land & Ferry Company. Completion of the trans-continental railroad in 1869 injected new vitality into California, and San Francisco had become the financial center of the West. The Pacific Mail Steamship Company had established regular routes to the Orient from San Francisco, and a thriving California grain trade filled the bay with ships from Liverpool and New England.

As grain ships were laid up in Carquinez Strait and Richardson's Bay waiting for the grain to be harvested or for the price to go up in home ports, their masters and crews became enamored of life in California. Many of the earliest settlers in Sausalito were British, who perhaps preferred the quiet country life to that of dynamic, raw San Francisco. Some were sent to represent British companies, some came from the vessels themselves. Others came to seek their fortunes in the legendary land of California. Most of the English residents of Sausalito were "second sons." That is, they came from landed wealthy English families and although they usually had sufficient annual stipends, they had no titles. The eldest son stood to inherit the title and property in England, leaving the other sons and daughters to seek their fortunes elsewhere. The men took positions in banking and brokerage houses, and the women often married American businessmen.

In the accompanying photo, the man perched on the new wharf gazes back at the first ferry landing at the foot of Princess Street. The ferryboat Princess rests at her pier.