By Jack Tracy and Larry Clinton, Sausalito Historical Society

Back in 2010, we ran Jack Tracy’s account of the political struggles between gamblers and reformers in early 20th century Sausalito. Most of the gambling involved off-track betting on horse races, at establishments euphemistically dubbed pool rooms — literally rooms where betting pools were organized. These rowdy saloons were hangouts for loafers, criminal types, and drunks.

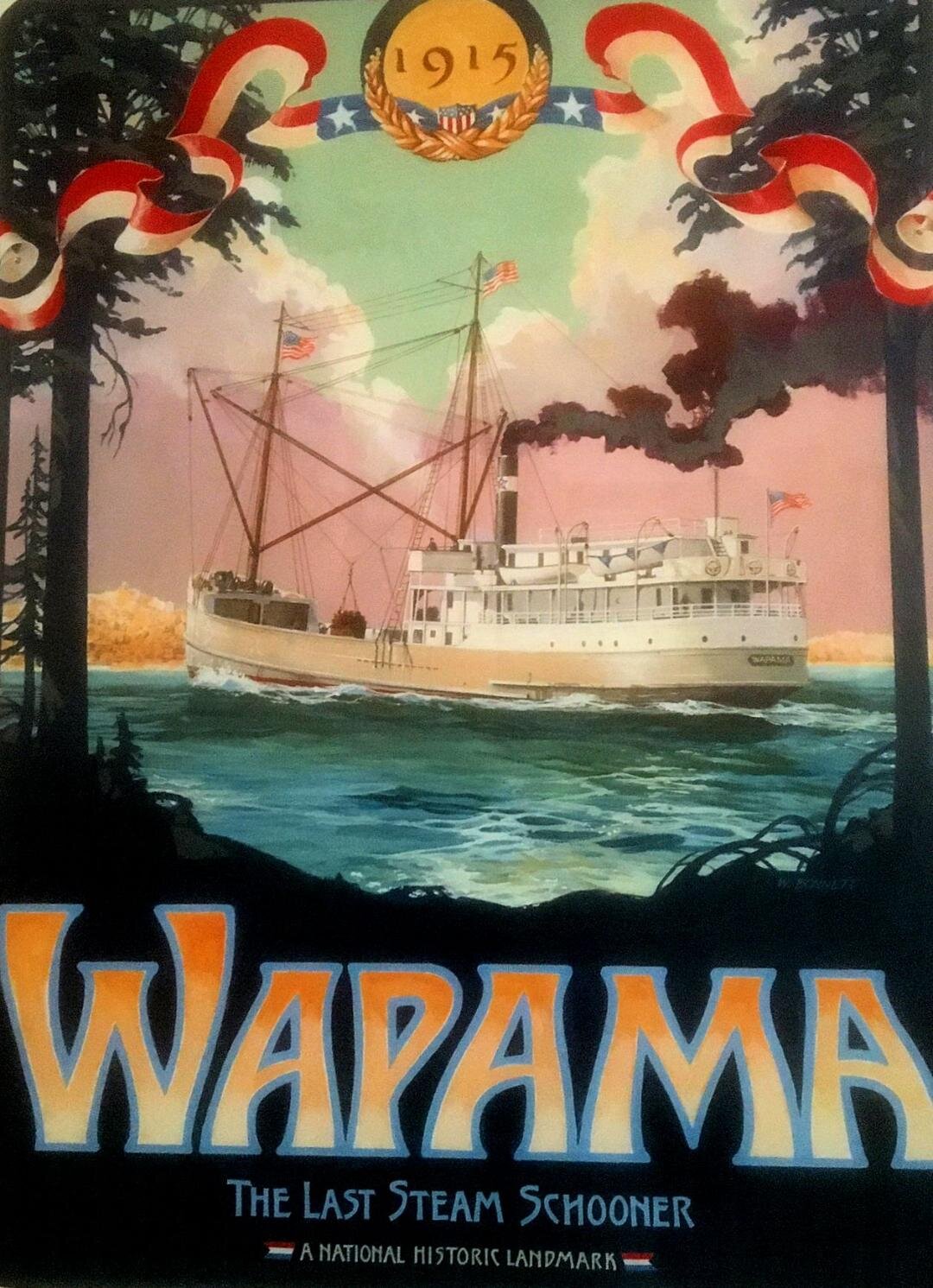

PHOTO FROM SAUSALITO HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Scipio Ratto stands behind his assistant “Babe” Malone inside the grocery store Ratto co-owned with John Mecchi.

In Tracy’s words, “Scipio Ratto in many ways exemplified the Sausalito reformers who took the town out of the hands of the gambling interests and gave it back to the residents, and who worked tirelessly over the years to improve life in their town.”

Mr. Ratto was an intriguing figure in Sausalito history, as evidenced in these lightly edited excerpts from Tracy’s book, Moments in Time:

He was born in San Francisco in 1869, son of a Mother Lode general store proprietor who came to California from Italy in 1852. Scipio's father ran two San Francisco bakeries and what few days off the family had were spent in Sausalito. It was on these picnic outings that Scipio fell in love not only with Sausalito but also with Angelena Antoni, whose parents had come over land to California during the Gold Rush.

When gold was discovered in the Yukon, Scipio Ratto set out for the Klondike. He arrived in Juneau in the summer of 1897, full of high hopes and big plans. He went up the Whitehorse River in search of gold. After almost a year of struggling with freezing cold, scurvy, wild rivers, lots of ice, and very little gold, Ratto made his way to Dawson City, then a scruffy boom town crowded with miners and merchants. He eventually found work in George Biber's general store in 1899. Like most others, he left the Yukon no richer than when he arrived.

In 1904 at age thirty-five, Scipio Ratto was ready to settle down. He married his sweetheart Angelena and moved to Sausalito, where he formed a partnership with John Mecchi in 1905

Downtown Sausalito resembled the rough and tumble mining camps of the Yukon when Ratto arrived. The streets were mud holes, rowdy drunks were common on Water Street, and the gambling rooms and saloons seemed like the principal business. Ratto and his wife became political activists, taking part in almost every effort to improve their town as well as rearing two daughters.

Reformers like Ratto continued to push for elimination of legalized gambling, and in 1909 the California Legislature outlawed off-track betting. The Sausalito poolrooms closed their doors. By that time most of the disreputable saloons were long gone, replaced by respectable family restaurants like the Arbordale. And the Board of Trustees was dominated by men who put civic pride and service above personal gain.

Ratto maintained a successful grocery business in Sausalito until he retired in 1935. He also helped form the Old Town Social Club, was an officer in the South Sausalito Improvement Club, and served as Assistant Chief of the Sausalito Volunteer Fire Department in 1912. He was a charter member of the Sausalito Lions Club and the Chamber of Commerce, and a member of the Native Sons of the Golden West for over forty years. In his spare time he served on the Sausalito School Board, from 1922 to 1940, and was a member of both the Eagles and the Elks Club.

Mr. Ratto died in 1951 at age 82.

Moments in Time is available through the Sausalito Library and at Sausalito Books by the Bay.