By Jack Tracy, Sausalito Historical Society

One hundred years ago, national prohibition came to Sausalito. In his book Moments in Time, Jack Tracy tells how it affected life hereabouts:

Sausalito's saloons and liquor stores closed; beer, wine, and whiskey disappeared from grocery store shelves as California and the nation began the thirteen-year experiment that ended in repeal.

PHOTO FROM MOMENTS IN TIME

Webb Mahaffy, center, preceded Herb Madden as Mayor. He and two hunting companions are shown swigging from a suspicious bottle, c. 1930.

At first, prohibition had very little impact on Sausalito. Most people who were so inclined had stocked up on their favorite beverages, and those with access to grain soon learned the brewer's art. The saloons reopened as "Soft Drink Parlors," where it was usually possible to get a little something to liven up a seltzer. Mason's Distillery in Sausalito, a major producer of whiskey, underwent some worrisome moments until its role under the Volstead Act was determined. Mason's continued to manufacture alcohol under federal license for medicinal and industrial purposes. By 1925 the Mason By-Products Company was producing 2 million gallons of denatured alcohol per year, nearly one-sixth of all the alcohol produced in the country.

In the early 1920s, Sausalito had only two policemen, making enforcement of prohibition impossible. It was about as easy to get a drink in Sausalito as it had been before prohibition. As in most of the country, it became fashionable and somewhat daring to visit "speakeasies" or underground saloons and to know a bootlegger by his first name. One Sausalito resident recalls that as a boy he made pocket money by collecting empty liquor bottles that had washed up on Marin beaches and selling them to local contacts. The bottles would probably turn up the next day with new labels proclaiming the contents to be "genuine" twelve-year-old Scotch.

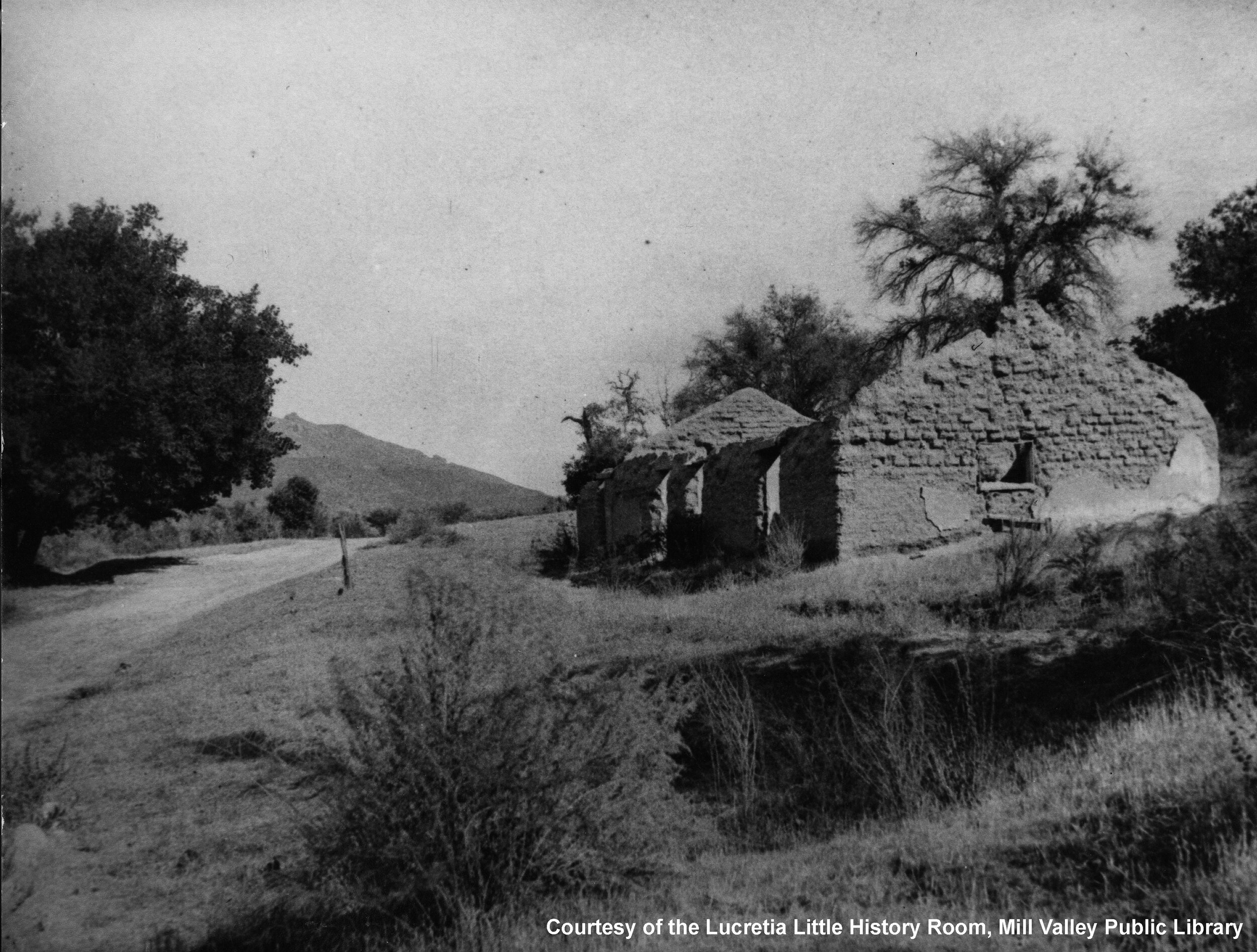

Canada, where sale of alcoholic beverages was still legal, was a major source of bootleg whiskey during prohibition. Marin County with its miles of unguarded beaches became a popular landing zone for whiskey smuggled in from Vancouver or for "moonshine" disguised as Canadian whiskey or Mexican rum. Soon Sausalito was the funnel through which bootleg alcohol passed to its destination in San Francisco's speakeasies. Knowing that a shortage of federal agents making random searches of vehicles on the San Francisco side of the bay meant little chance of getting caught, bootleggers brazenly loaded their liquor-filled autos and trucks onto ferryboats in Sausalito.

Because the prohibition law was unpopular, local authorities received little help in enforcing it from

residents. When a speakeasy or hidden still was raided, it was usually because the bootleggers got too bold. The Soft Drink Parlor Walhalla was raided in 1921. There had been reports of considerable nighttime activity at a trap door leading from Walhalla's floor to the bay beneath, where small boats could be hidden among the pilings. Annie Lowder, proprietor of the Walhalla, was carried off kicking and screaming after agents found 478 quarts of home-brew and "a large quantity of jackass brandy with a vigorous kick." The Sausalito Cash Grocery on Princess Street was raided in 1926 by Town Marshall Al O'Connor and Officer Manuel Menotti after neighbors complained of customers coming and going all night long. Sure enough, a small-time bootlegging operation had exceeded the bounds of propriety and called attention to itself.

Most people treated prohibition lightly. Alcohol was served at most social events in private homes, and often at club meetings. Jokes circulated about the latest "imports" and about the unprecedented number of drug store prescriptions for high alcoholic content cough medicine. But the lightheartedness diminished as incidents of serious illness and death from "bum booze" increased. An even more sinister side to prohibition developed in the mid-1920s when organized crime made bootlegging its number one activity. The Vo!stead Act was a dream come true for big-time gangsters. It drove an indispensable consumer product underground, creating a bonanza for criminals who had the money to buy and deliver large quantities of alcohol.

A national underground network of alcohol distribution developed, with the local user knowing only his immediate supplier, the friendly neighborhood bootlegger. Increasingly determined to crack down on gangsterism, federal agents arrested as many links in the chain of distribution as possible, often with some surprising results. Sausalito's mayor, John Herbert Madden, learned firsthand about the federal crackdown on prohibition violators. He was accused of repairing the vessel Principio in San Pedro in 1924 with the knowledge that the ship was a known "rumrunner" owned by San Francisco bootlegger Joe Parente. Madden denied the charge, claiming that his boatyard repaired all manner of boats including Coast Guard patrol vessels, and that in many cases he did not personally examine the vessels. He was found guilty of conspiracy in 1926, sentenced to two years' imprisonment at McNeil Island, Washington, and fined $5,000. Madden continued to profess innocence in the affair; nonetheless, he served fifteen months of the sentence before his release. He was again elected to the City Council and in 1936 chosen again as Mayor of Sausalito.